In the nineteenth century the epitome of grace and elegance – and sexual frisson – was to be found in the Romantic Ballet.

Ballet had originally developed in sixteenth century Italy as a ritualised Court pass time and was adopted by royal courts through out Europe. Early ballet costumes reflected the elaborate styles of the day.[1]

Industrial developments in the nineteenth century saw a revolution in fabric manufacture, allowing for lighter more gauzy fabrics to be mass produced. This manufacturing development caused a revolution in ballet costumes.

Many of these ethereal dancers became feted stars of the day, but the glamour and fame of these ballet girls came at a high price and it could sometimes be fatal.

The Romantic Ballet

1832 Marie Taglioni brought the house down when she performed La Sylphide in a frothy concoction of white tulle. Her performance cemented the gauzy white tutu as the derigueur costume of the Romantic Ballet. It was an ideal fabric for depicting the typical dryads, nymphs and other supernatural creatures that populated the ballet blanche in the nineteenth century, and it also looked divine by gaslight.

The new costume was made of much lighter fabric and revealed more of the ballet dancer’s legs. But this change from the earlier, heavier, corseted and more restrictive costumes of earlier centuries was not caused by vanity – it was necessitated by the higher jumps and pointe work that ballet dancers were now expected to perform as the technique had evolved.[2][3]

Alison Matthews David notes that the changes were considered highly scandalous, and many men attended the ballet for less than artistic reasons – after all, these aerial sylphs were all sexually available, for the right price. The sexual market-place aspect of the ballet had the knock on effect of pushing ballerinas to the front of the stage, nearer to the footlights and their potential patrons, and inadvertently placing them much closer to danger.

Despite the other-worldly, untouchable quality of Romantic Era ballerinas, the cold hard truth was that ballet girls were often lower class girls sold by their parents to ballet companies. They were underfed, over-worked and often sexually exploited. Yet they dared not complain about their dangerous and exploitative conditions or risk their livelihoods. [4]

Dancing with Death

Consequently ballerinas danced with death on a daily basis, so much so that they regularly incinerated both themselves and their audiences in truly incendiary performances. The combination ballet and firey death was so ingrained in the popular imagination that tickets to the ballet were macabrely nick-named ‘tickets to the tomb’ due to the risk of death by fire, smoke inhalation or toxic gases [5]. Perhaps this was one of the aspects of the ballet that appealed to the well developed sense of morbidity of the Victorians – ballet at its extreme could encompass both sex and death, an alluring combination.

Media and literature of the day also took a morbid, and at times misogynistic, delight in reporting fatal tragedies when they struck, often lingering on the terrible injuries of the unfortunate girls.

In 1856 Theophile Gautier’s novel Jettatura described the death of a ballerina:

“The dancer brushed that row of fire which in the theatre separates the ideal world from the real; her light sylphide costume fluttered like the wings of a dove about to take flight. A gas jet shot out its blue and white tongue and touched the flimsy material. In a moment the girl was enveloped in flame; for a few seconds she danced like a firefly in a red glow, and then darted towards the wings, frantic, crazy with terror, consumed alive by her burning costume.”

This is no artistic flight of fancy, Gautier was inspired by the death of real life ballerina Clara Vestris Webster at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London, in 1844.

Clara had been playing Zelika, a royal slave, in the ballet The Revolt of the Harem. In a playful and erotic harem bath scene, she had been throwing water over other ballerinas, when her skirts caught fire on one of the sunken lights being used to represent the bath. Terrified, the other dancers did nothing to help – fearing the same fate. Gautier, writing her obituary for the Paris papers, in a spectacular display of misogyny and callousness said:

“it was said that she would recover, but her beautiful hair had blazed about her red cheeks, and her pure profile had been disfigured. So it was for the best that she died.”

The Media also revelled in the gory details of the girl’s death, reporting that:

“The body was so much burnt that when it was put into the coffin, the flesh in parts came off in the hands of the persons who were lifting it, and on the same account it could not be dressed.” [6]

As with many similar cases, the inquest found the death to be an accident and attached no blame to the theatre, even though the fire buckets by the stage had been empty.

Clara’s death did encourage more research into the fire-proofing of dresses. Queen Victoria also helped instigate research into flame-proofing fabrics even putting the royal laundry at the disposal of Dr Alphons Oppenheim and Mr F Versmann. They found that treating fabrics with Tungstate of Soda and Sulphate of Ammonia solution made fabrics safer. However there were drawbacks: once washed, the fabrics had to be re-treated. Despite these promising findings, no safety legislation or regulations were enacted in Britain.

In 1861 the beautiful Gale sisters, Ruth, Cecilia (known as Zela), Hannah and Abeona (know as Adeline), took the USA by storm. The English ballerinas toured the states wowing audiences wherever they went; however it was their final venue that has made them famous: The Continental Theatre in Philadelphia.

In August 1861 Actor Manager William Wheatley leased the theatre on Walnut Street. He spared no expense going so far as importing a special effects expert and the beautiful Gale sisters from England. The Ballerinas had their dressing room directly above the stage, it was fitted out with mirrors with gas jets next to them, in order to maximise the light they gave off.

On the evening of the 14 September 1861 an audience of 1500 people filled the Continental Theatre for the first night performance: Shakespeare’s The Tempest, adapted as a ballet. Many no doubt hoping for a glimpse of the fine legs of the beautiful Gale sisters as they floated about the set, the audience was unprepared for the horror about to unfold just off stage.

At the end of Act one, the Gale sisters and the corps de ballet had to flit up the narrow staircase to their dressing room 50 feet above the stage – a quick change was required for the next scene. While the show continued beneath them, the Gale sisters began to change costumes. Ruth climbed upon a settee to retrieve her gauzy tarletan costume, but the hem caught on the gas jet and within seconds Ruth was ablaze. In terror, Ruth ran through the dressing room and dashed herself into a plate glass mirror, adding to her horrific injuries. Her sisters, in trying to help her were caught up in the blaze. [7]

In the panic and confusion they flung themselves from the window onto the street below. A Miss McBride ran flaming on to the stage and fell into the orchestra pit, where she was eventually put out by stagehands.

Initially Wheatley had called for the curtain to fall and asked the audience to remain seated, however he soon realised the severity of the unfolding tragedy and ordered an evacuation. It is remarkable that no members of the audience were killed during the fire.

That was not the case with the ballerinas. Burned and broken ballerinas littered the streets outside the theatre as police, doctors and bystanders desperately tried to help. Harper’s Weekly described the scenes as ‘most piteous and agonising’. The burnt ballerinas were taken to taverns and hotels, and eventually by carriage to the Pennsylvania Hospital. With little or no pain killers available, the journey must have been agony. Over a four day period between six and nine ballerinas, including all of the Gale sisters, lost their lives. [8][9]

At the Coroner’s Inquest William Wheatley was cleared of all wrong-doing, and it must be said that he and his wife did all they could after the tragedy to pay medical bills and funeral costs for the lost girls. Wheatley also erected a memorial to them in Mount Moriah Cemetery. However, one wonders, in his no-expenses spared refit of the Continental, how much expense was spared for safety measures? [10]

The dangers faced by ballerinas in their highly flammable costumes was not entirely ignored by the authorities, in France an Imperial Decree was issued in 1858 which attempted to introduce flame-retardant fabrics for ballet dancers. When the fabrics were treated it had the unfortunate side-effect of rendering the formerly ethereal white tutu heavy, dingy and stiff. The safer tutu, where it was available, was often rejected outright by those it was intended to protect, as the case of Emma Livry shows.

Emma Livry, the illegitimate daughter of a ballet dancer and a baron, was the last great star of the Paris Opera Ballet from her debut in 1858 until her death in 1863.

She had been offered a drab flame retardant dress, but Emma simply refused to wear it. Her attitude may seem blase, but it cannot have been uninformed. There were too many high profile cases for Emma not to have been aware of the very real dangers faced by ballerinas in their flimsy tulle tutus.

Emma’s unintended final performance was on 15th November 1862, during rehearsals for the ballet opera La Muette de Portia. Sitting down, she raised her tutu above her head to prevent crushing the delicate fabric, the rush of air this created caused a nearby gas light to flame and this set light to her tutu. The fire blazed to three times her height. Engulfed in flames, she ran across the stage several times before she was finally caught, and the fire put out.

Her injuries were catastrophic, Emma suffered 40% burns, her stays were burned on to her, although her face was untouched. She survived for eight months eventually dying on 26th July 1863 of Septicaemia caused by her burns. She was barely 21. Shortly before her death she was still unrepentant, saying of the flame-retardant materials, “Yes, they are, as you say, less dangerous, but should I ever return to the stage, I would never think of wearing them – they are so ugly.” [11]

Bonfire of Vanities

It is important to remember that there were a lot of reasons for Emma, and others like her, to have made such a fatal choice of costume. It is disingenuous and a little to easy to attribute it to the vanity of these girls.

Flame-proofed tutus were stiffer and dull looking. Tulle tutus looked celestial, glowed softly in the low lights of the theatre, and made the dancers look like sylphlike creatures from another world. Dancers were poor girls, worked to exhaustion for minimal wages. They depended upon captivating the audience, in particular wealthy men who might become their patrons and lovers, they needed to look stunning to be marketable. If they did not bring in paying punters, there was a real chance they would end up back in the gutter, starving. The irony is that they risked their lives in order to survive.

Responsibility must also rest with governments who either did not bother with health and safety legislation, or where they did so, they failed to enforce it or hold anyone to account. More could have been done to make theatres safer places for ballerinas, fire blankets and fire buckets are simple measures but could have been effective safety measures, but too often these measures were overlooked with catastrophic consequences.

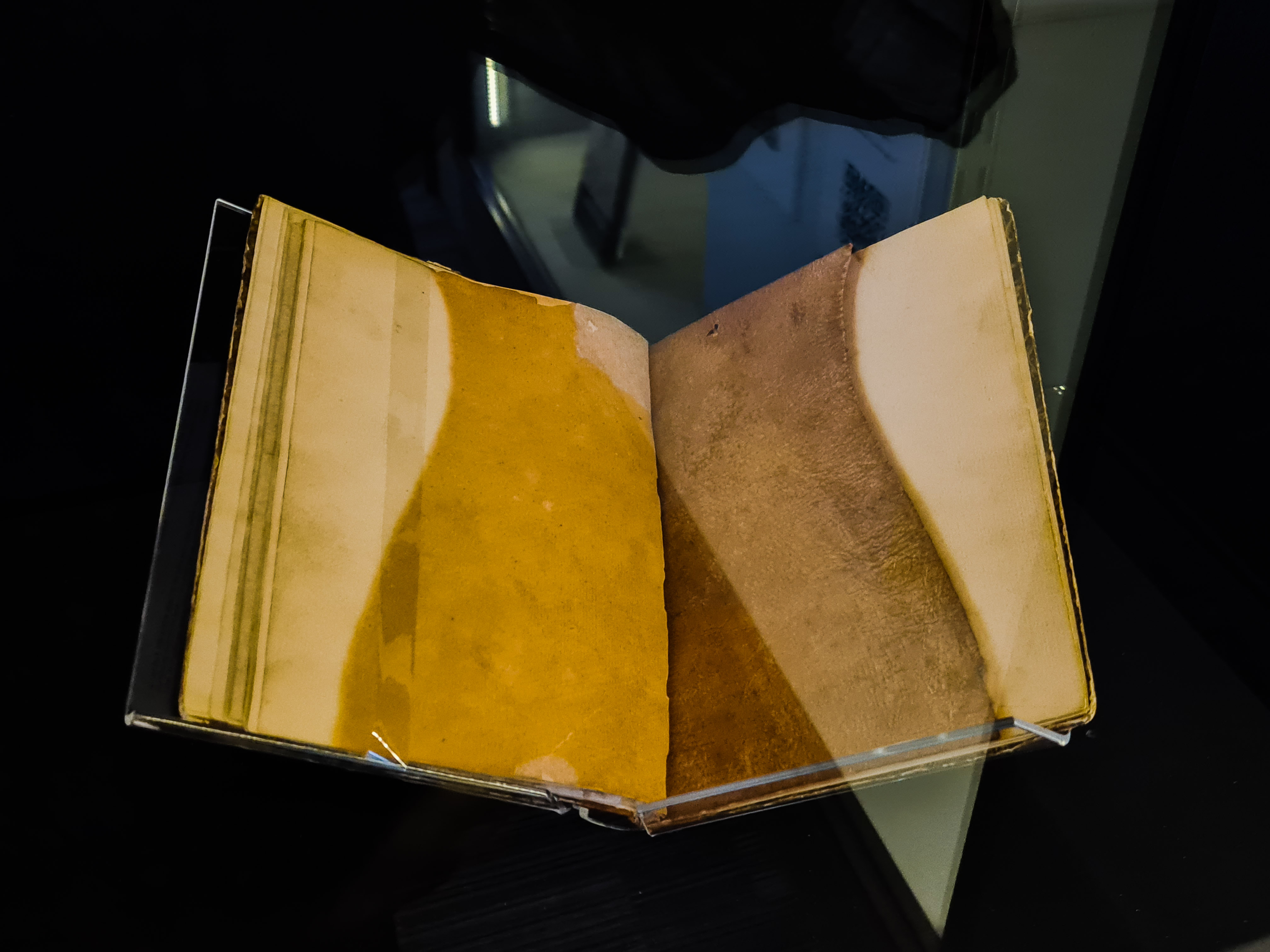

Sarcophagus containing Emma Livry’s burnt tutu. Paris Bibliotechque National via Fashion Victims.

Epilogue

The Tragic Gale sisters found their final resting place in Mount Moriah Cemetery. Though their grave stone is worn and faded now, the New York Clipper reproduced the text of their memorial:

“Over the deep broad grave in Mount Moriah Cemetery, Philadelphia, in which repose in eternal silence the four sisters Gale, a memorial tablet has been erected by the subscription of many kind friends who knew the poor girls in their pure life. And upon it has been graven the following inscriptions :

On one side –

With a mother’s tearful blessing They sleep beneath the sod, Her dearest earthly treasures Restored again to God!

And upon the other –

IN MEMORIAM Stranger, who through the city of the dead With thoughtful soul and feeling heart may tread, Pause here a moment – those who sleep below With careless ear ne’er heard a tale of woe: Four sisters fair and young together rest In saddest slumber on earth’s kindly breast; Torn out of life in one disastrous hour, The rose unfolded and the budding flower: Life did not part them – Death might not divide They lived – they loved – they perished, side by side. O’er doom like theatre let gentle pity shed The softest tears that mourn the early fled, For whom – lost children of another land! This marble raised by weeping friendship’s hand To us, to future time remains to tell How even in death they loved each other well.”

Sources and Notes

bellanta.wordpress.com/2010/02/20/this-holocaust-of-ballet-girls/ [8]

civilwartalk.com/threads/flames-in-gauze-and-crinolines-the-gale-sisters-last-dance-together-sept-14-1861.140489

(The above includes extracts from Frank Leslie’s 1861 editorial on the Gale sisters demise). [[7] [11]

http://friendsofmountmoriahcemetery.org/cecilia-ruth-adeline-and-hannah-gale-ballerinas/

Daily Dispatch, October 1 1861, The recent terrible accident at the Continental Theatre in Philadelphia, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2006.05.0285%3Aarticle%3Dpos%D11

Matthews David, Alison, 2015, ‘Fashion Victims The Dangers of Dress Past and Present’ [4]-[6] [9]

ozy.com/flashback/the-ballet-girls-who-burned-to-death/71244 [11]

The Public Ledger, 18 March 1845 Shocking Death of Miss Clara Webster: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=59&dat=18450318&id=cSA1AAAAIBAJ&sjid=GicDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6310,1978758&hl=en

http://www.tutuetoile.com/ballet-costume-history/ [1]

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/o/origins-of-ballet/ [2][3]

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/r/romantic-ballet/ [2][3]

All links were correct when the article was published.

Leave a Reply