Dark tourism

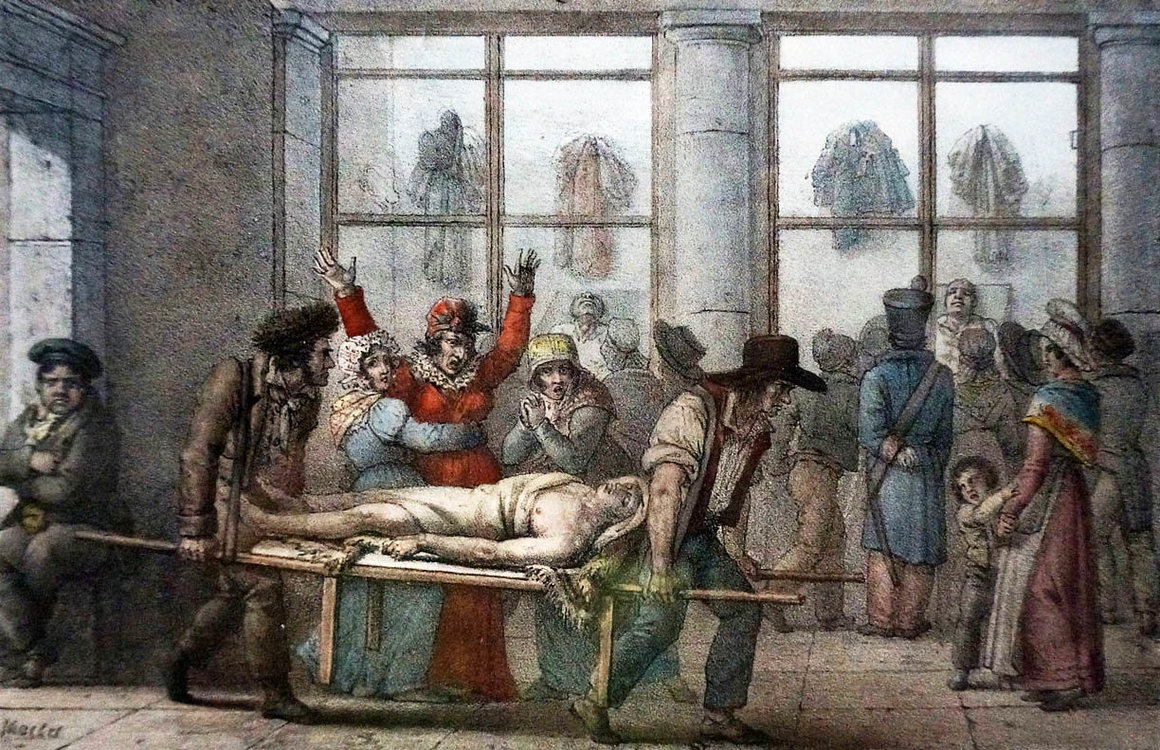

Anyone familiar with David Farrier’s recent Netflix Series Dark Tourist, will know that for a certain element of society, tourism isn’t about sun, sea and sand but about exploring the macabre, dangerous or disturbing. Far from being a new trend, this phenomena has long history. In the nineteenth century the Paris Morgue was an unlikely, but popular, attraction. Many an English traveller would turn their steps away from the famous sights of that most romantic of cities and follow the crowds towards the best free show in town.

In Thérèse Raquin Zola perfectly captures the popular appeal of the morgue, with all of its grisly drama and spectacle:

“The Morgue is a spectacle within the reach of all pockets, free for all, the poor and the rich. The door is open, anyone who wishes enters. There are fans who make detours so as not to miss a single representation of death. When the slabs are empty, people leave disappointed, robbed, mumbling under their breath. When the slabs are well furnished, when there is a good display of human flesh, the visitors crowd each other, they provide cheap emotions, they scare one another, they chat, applaud or sniffle, as at the theatre, and then they leave satisfied, declaring that the Morgue was a success, that day”

The Paris Morgue was regularly featured in journals and travel books of the era. While there was often there was an undercurrent of moral disapproval at the voyeurism inherent in the morgue’s attraction, it’s popularity as a free public spectacle knew no bounds.

But how did a civic institution become a public spectacle and was there a more serious purpose behind this most macabre institution?

A Stinking Pestilent Place

Every city has a problem with what to do with the unidentified and unclaimed dead. In Paris the Medieval period, the Order of St Catherine fulfilled this function. Later, in the reign of Louis XIV, the practice of displaying the dead to identify them was established. The very word morgue comes from an archaic verb morguer which, as Vanessa R Schwartz explains, means to stare or have a fixed and questioning gaze, which would seem very appropriate under the circumstances.

In 1718 the Dictionaire de l’Academie defined the Paris Morgue as ‘a place at the Chatelet [prison] where dead bodies that have been found are open to the public to view in order that they be recognised’ and which was composed of ‘dead bodies found in the street and also found drowned’ [p49]. Indeed, drowning victims would be the staple of the morgue for most of its existence.

Despite the public function of such morgues, those historically attached to prisons were by no means a clinical setting for viewing the dead. Corpses were often tossed on the ground in piles, left to putrefy while unfortunate visitors had to to breath in the noxious vapours as they tried to identify them. Adophe Guillot described the Basse Geole as ‘[..] a stinking pestilent place with little of the respect death deserves ‘[1].

The Chalelet Prison in Paris fell-foul of its royal connections during the French Revolution and was closed in 1792. But not before hosting the grisly remains of the 7 prison guards killed during the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789.

The Temple to the Dead

The growing urbanisation of Paris in the nineteenth century, which saw more people living cut off from their traditional communities, increased the chance of people dying anonymously amongst strangers. This in turn created an administrative problem of how to identify the masses of unidentified corpses that kept turning up on the streets and in the Seine.

In 1804, a new morgue was built by order of the Napoleonic Prefect, in order to address this problem. The purpose-built morgue was sited on the Ile de la Cite, at the Quai du Marche, on the corner of Pont St Michel, it was close to the river – the supplier of so many corpses destined for display in the morgue. This new classical building was purpose-built in the centre of the administrative district –it was very visible, sited on a busy road and close by the Police HQ and courts. All elements crucial to its civic function – the river to bring the bodies, the public to identify the bodies, the police to solve crime, the courts to punish the guilty.

Although this new specialised building was far better than what went before, and drew in thousands of spectators, it still had its problems; there was no private entrance for delivery of corpses, the morgue had a terrible chemical smell, and there was a huge population of large grey rats that frequented the area.

the Morgue and the Media

In the 1850’s Napoleon’s prefect of the Seine, Baron George Haussmann had grand plans for Paris. Haussmann redeveloped (some say ‘disemboweled’) the crowded Medieval Isle de la cite, to build the new more spacious Boulevard Sebastopol. The old morgue, in the heart of Medieval Paris, fell foul of ‘Haussmannization’ and was demolished. In 1864 a new and improved morgue was built behind Notre Dame Cathedral on the quai de l’Arche Veche.

The new morgue was much larger than the old, with a large Salle du Public (exhibition room) and it was endowed with more advanced facilities including rooms for autopsies, registrar and staff, a laundry (for the clothing of the deceased) and a more discreet rear entrance for corpses. By the 1870’s photography was being utilised when corpses were no longer suitable for display, and by the 1880’s refrigeration was introduced. However, despite these sound scientific improvements and the emphasis on the civic duty of displaying the corpses to the public in order to aid identification, there remained a huge element of sensation and entertainment in a visit to the morgue. In the public imagination, which was fuelled by the popular press of the day, the morgue was intrinsically linked to suicide, murder and human tragedy.

A visitor to the new morgue in the 1860s would have been in for a grand spectacle of everyday drama. If the body on display was a cause celebre a visitor might have to queue for hours to gain entrance. In a single day tens-of-thousands of men, women, children, of all classes, might come to view the latest media sensation, such happened in the cases of L’affaire Billoir in 1876 & the Mystere de la rue Vert Bois in 1886. In the first case a man dismembered his lover, her body was fished out of the Seine in two packages, while the second related to an 18 month old girl found dead at the foot of a staircase. Both cases caused an ongoing media sensation. Keeping the cases in the news kept the crowds coming to the morgue in their thousands, to view the corpses and speculate on the circumstances of their demise. Ironically, in the Billoir case, while tens of thousands of visitors thronged the morgue to view his victim’s remains, less than 600 people attended his public execution. [2]

A visit to the morgue

The layout of the building created a kind of peep show for the crowds as they patiently jostled forwards. Billboards and posters advertised the corpses within, visitors were ushered in single file in one direction. Corpses were displayed behind vast plate-glass windows, draped with long green curtains which only succeeded in adding to the theatrical nature of the experience.

Bodies were laid out in two rows of six, naked but for a cloth covering their modestly, items belonging to them were hung up near them. In some cases, such as the Rue Vert Bois case and Mystere de Suresnes (two young girls retrieved from the Seine, triggering speculation that they might have been sisters), drama was added to the tragedy by posing them on chairs, in a kind of tableau, rather than on the cold hard slab. Due to initial mis-identification in the Suresnes case, these little corpses had to be put back on display, even after the bodies began to significantly decay, which must have been both a very macabre and a very sad sight. And as such, it was just the kind of spectacle the crowd came for: combining sensation, sentimentality and speculation.

Voyeurism and Moral Hygiene

Before refrigeration was introduced in the 1880s a constant drip of water was fed from pipes above each slab, in order to keep the bodies fresh. It is debatable how well this worked, and sometimes, such as that of the woman in the Billoir case, the body began to deteriorate and a wax model had to be substituted for the real thing.

Most of the bodies displayed were male, although women and children were also displayed (and were often the focus of intense media interest). Zola famously wrote of the morgue in his novel Therese Racine, where he touches on the erotic undertones of viewing a corpse:

“Laurent looked at her for a long time, his eyes wandering on her flesh, absorbed by a frightening desire.”

Contemporary moralists were particularly worried about threats to the risk to ‘moral hygiene’ entailed in a visit to the morgue. In particular, they feared the uncontrolled voyeurism of female visitor, women being considered the ‘weaker’ sex morally as well as physically. A visit to the morgue gave women access to view near naked male bodies. Not only women, but children were also frequent visitors to the morgue, and the effects of visiting such a macabre site on children were also a cause of public concern. None of this moral panic, however, diminished the crowds thronging the streets to gain entrance to the Morgue.

While it is true that some visitors attending the morgue might imagine that perhaps they could assist in the identification of one of the unfortunates on display, this was not the prime motive for most visitors. As Schwartz has argued, they were attending for the drama of the everyday, an interest both generated and sensationalized by the media. It was free theatre. Who knows, you might be lucky enough to witness the murderer, not quite returning to the scene of the crime, but brought low by conscience after being faced with his victim. This was not so far-fetched a scenario, the police did sometimes bring the accused to the morgue to gauge their reactions in a ‘day of confrontation’ [3], Clovis Pierre writing in Le Figaro described these events as ‘[a] sensational show’. It also gave the public the opportunity to participate in the drama directly. A contemporary writer, Firmin Maillard, exclaimed ‘who needs fiction when life is so dramatic’ [4] – this was a huge element of the Morgue’s continued popularity.

It is interesting to note that the voyeurism inherent in a visit to the morgue extended beyond the corpses to its living denizens as well. Often better-off visitors came to the morgue as much to gawp at the lower classes at play, as at the deceased (whom they would have very little chance of being able to identify). One factor in common with those whose death resulted in the stigma of public display in the morgue, was that they were nearly all members of the lower classes, the poor and dispossessed of Paris were far more likely to die alone or remain unidentified. [5][6]

Innovation and Social Engineering

But of course the morgue served as far more than a public spectacle. Alan Mitchell in his article The Paris Morgue as a Social Institution in the Nineteenth Century, sees it as a positivist force, helping to revolutionise forensic medicine and policing – introducing refrigeration, pioneering forensic photography, focusing on autopsies.

It could also be seen has an attempt at social engineering: a way of turning the active and dangerously mob, who had engaged in revolutionary and subversive activity in the eighteenth century and the earlier parts of the nineteenth century, into passive and more tractable group of spectators. [7] Whether as deliberate policy or not, the morgue could be seen to have been a part of a wider social and political agenda in de-politicising the masses. Setting the foundation for today’s passive consumer culture, easily distracted from the bigger issues by the latest sensation or spectacle.

The final curtain

The Morgue was finally closed in 1907 due to concerns with moral hygiene and a desire to professionalize the Morgue and its functions. Its replacement was the Medico-legal Institute which remains to this day. However, the Paris Morgue of the past should not be dismissed simply as grisly voyeurism (although that certainly did play its part).

The Morgue represented a way for the authorities to institutionalise death which contributed to the improvement in scientific and forensic techniques. It also highlighted the drastic changes in rapidly industrialising societies. While the nineteenth century is famous for its obsession with the Good Death, the morgue showcased the alternative, the Bad Death. Showing death as anonymous, ignominious, public, and, the antithesis of the Good Death, an ephemeral popular entertainment.

This de-sacralisation of death, turning it from a private religious contemplation of the eternal into a public spectacle, heavily linked to current events was fed by the popular press, whose influence on popular culture was becoming more pervasive as the century progressed. It may also have been a way of allowing an increasingly secular, urbanised and disconnected people to experience the horror, the drama, and the hidden tragedies of everyday lives – from a safe distance. In some ways, not much has changed.

Photograph of the Paris Morgue public viewing room. Source unknown. Via Cult of Weird.

Sources and notes

http://www.cultofweird.com/death/paris-morgue/

Mitchell, Alan, ‘The Paris Morgue as a social institution in the nineteenth century’ Francia 4 1976 (581-96) [6]

Schwartz, Vanessa, R, 1998 ‘Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris’ University of California Press [1]-[5] and [7]

Tredennick, Bianca, http://muse.jhu.edu/article/478521 – Some Collections of Mortality: Dickens, the Paris Morgue, and the Material Corpse, The Victorian Review.

Leave a Reply